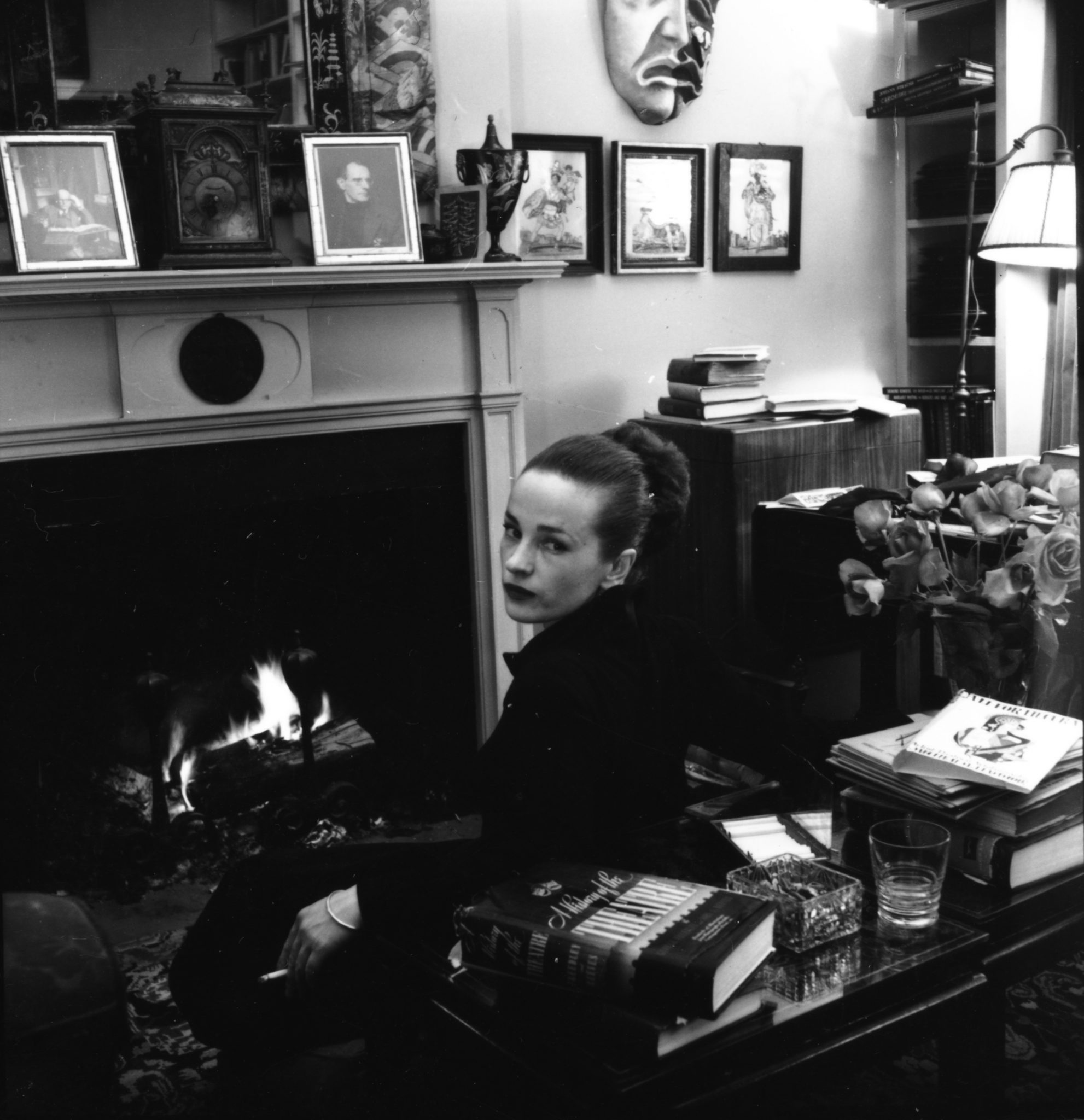

Maeve Brennan… helped put New York back into The New Yorker, and has written about the city of the sixties with both honesty and affection… She is constantly alert, sharp-eyed as a sparrow for the crumbs of human event, the overheard and the glimpsed and the guessed at, that form a solitary city person’s least expensive amusement.

— John Updike

Maeve Brennan’s Notes from The New Yorker

“Now when I read through this book I seem to be looking at snapshots. It is as though the long-winded lady were showing snapshots taken during a long, slow journey not through but in the most cumbersome, most reckless, most ambitious, most confused, most comical, the saddest and coldest and most human of cities. Sometimes I think that inside New York there is a Wooden Horse struggling desperately to get out, but more often these days I think of New York as the capsized city. Half-capsized, anyway, with the inhabitants hanging on, most of them still able to laugh as they cling to the island that is their life’s predicament.”

—from the Author’s Note in the original edition of The Long-Winded Lady (1969)

“Maeve Brennan’s act of rebellion, as the long-winded lady, was to write New York as the city of a woman with ordinary things to do in the morning and with a love, in the mid-afternoon, of sitting by herself in little restaurants, staring at people, eavesdropping on their conversations while pretending to be absorbed in a book. She made no apologies for her nosiness, and she made no apologies for the defiantly quotidian detail of her errands, of her routes on foot, of the random thoughts and wonderings and memories which popped into her head and back out again. ‘Well, there you are, in case you’ve paid any attention,’ the first column ended, in 1954. ‘It was the moment of no comment,’ ended a 1962 piece, about the experience of observing two passing nuns from a restaurant window, and then, in case the strangely unyielding conclusion had not baffled readers sufficiently the first time around, ‘It was the moment of no comment,’ again. On a page of The New Yorker which had always been about charm—a charm possible because it came from a place of easy privilege—Brennan created a persona who was still charming, but also a challenge. She took the reader deep into her experience of their shared city, with a specificity of location and neighbourhood which, sixty years later, still makes a New York reader feel as though they are walking with her through these very streets, past these very buildings, into this very zone with its stubborn personality—but she also makes the reader feel, frequently, as though they have slid into the opposite chair at her one-top and are being stared at in a way that says, Go home.”

—from Belinda McKeon’s new introduction

Praise for The Long-Winded Lady:

I don't know whether in Ireland she is considered an Irish writer or an American. In fact, she is both, and both countries ought to be proud to claim her.

— William Maxwell